Binary Numbers

A binary digit, called a bit, has two values: $0$ and $1$.

Discrete elements of information are represented with groups of bits called binary

codes.

For example, the decimal digits $0$ through $9$ are represented in a digital system with a code of four bits, the number $7$ is represented by $0111$. How a pattern of bits is interpreted as a number depends on the code system in which it resides.

To make this distinction, we could write $(0111)2$ to indicate that the pattern $0111$ is to be interpreted in a binary system, and $(0111){10}$ to indicate that the reference system is decimal.

a way of representing numbers using a specific base (radix). Each digit in a number has a position, and its value depends on the base of the system:

The (Decimal) or (Base-10) or (Denary) System

This is the system we use daily. It has 10 digits: $0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9$ The value of a number depends on its position.

Example: $7392$

- $7 × 10^3$ (thousands place)

- $3 × 10^2$ (hundreds place)

- $9 × 10^1$ (tens place)

- $2 × 10^0$ (ones place)

So

$7392 = 7 × 1000 + 3 × 100 + 9 × 10 + 2 × 1 = 7392$

The (Binary) or (Base-2) System

Computers use binary (base-2) because they operate with only two states 0 and 1

every binary number is expressed in terms of powers of 2

Example: $11010.11$

$1 × 2^4 + 1 × 2^3 + 0 × 2^2 + 1 × 2^1 + 0 × 2^0 + 1 × 2^{-1} + 1 × 2^{-2}$

- $1 × 16 = 16 $

- $1 × 8 = 8 $

- $0 × 4 = 0 $

- $1 × 2 = 2 $

- $0 × 1 = 0 $

- $1 × 0.5 = 0.5 $

- $1 × 0.25 = 0.25 $

So

$16 + 8 + 0 + 2 + 0 + 0.5 + 0.25 = 26.75$

$(11010.11)2 = (26.75){10}$

The (Hexadecimal) or (Base-16) System

The hexadecimal system is another number system used in computing. It is called Base-16 because it has 16 possible digits. The letters A to F represent numbers 10 to 15 in decimal:

0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, A, B, C, D, E, F

Each digit is multiplied by a power of 16 (the base):

$B65F_{16} = (11 × 16^3) + (6 × 16^2) + (5 × 16^1) + (15 × 16^0)$

- $11 × 4096 = 45056 $

- $6 × 256 = 1536 $

- $5 × 16 = 80 $

- $15 × 1 = 15$

So

$45056 + 1536 + 80 + 15 = 46687$

$(B65F){16} = (46687){10}$

Other Number Systems

| Base (Radix) | Name | Uses |

|---|---|---|

| Base-3 | Ternary | Some theoretical computing models and balanced ternary systems. |

| Base-4 | Quaternary | Used in some genetic algorithms and quantum computing research. |

| Base-5 | Quinary | Found in some ancient cultures and abacus systems. |

| Base-6 | Senary (Hexary) | Some mathematical applications, used by the human hand (counting with one hand using the thumb). |

| Base-7 | Septenary | Rarely used, but found in some ancient calendars. |

| Base-8 | Octal | Used in early computing, file permissions in UNIX, and compact representation of binary. |

| Base-9 | Nonary | Occasionally used in some mathematical puzzles. |

| Base-11 | Undecimal | Rare, but has been considered in some numeral systems. |

| Base-12 | Duodecimal (Dozenal) | Used in traditional measurement systems (dozen, feet-inches) and advocated for better fraction division. |

| Base-20 | Vigesimal | Used by the Mayan and Aztec civilizations, also seen in some languages for counting. |

| Base-24 | Quadrovigesimal | Used in some encoding and encryption techniques. |

| Base-32 | Duotrigesimal | Used in Base32 encoding (data encoding in computing). |

| Base-36 | Hexatrigesimal | Used in URL shorteners and compact representation of alphanumeric IDs. |

| Base-60 | Sexagesimal | Used in time (60 seconds, 60 minutes), angles (360 degrees), and ancient Babylonian mathematics. |

Unusual & Specialized Bases

| Base | Name | Uses |

|---|---|---|

| Base-64 | Base64 Encoding | Used in data encoding for transferring files and email attachments. |

| Base-256 | Extended Binary | Used in character encoding (ASCII, Unicode). |

| Base-1 | Unary | Used in tally marks and theoretical computing. |

Important Powers of 2 (in Computing)

| Power | Value (Bytes/Bits) | Common Name | Range (0 to 2^(bits) - 1) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2⁰ | 1 bit | Bit (smallest unit) | 0 to 1 |

| 2¹ | 2 bits | Crumb (rarely used) | 0 to 3 |

| 2² | 4 bits | Nibble or (Nybble) | 0 to 15 |

| 2³ | 8 bits (1 byte) | Byte or (Octet) | 0 to 255 |

| 2⁴ | 16 bits | Word (16-bit systems) / Half-word (32-bit) | 0 to 65,535 |

| 2⁵ | 32 bits | Word (32-bit CPUs) / Double-word (16-bit) | 0 to 4,294,967,295 |

| 2⁶ | 64 bits | Quad-word / Long-word | 0 to 18,446,744,073,709,551,615 |

| 2⁸ | 256 bits | 0 to 2²⁵⁶ - 1 | |

| 2¹⁰ | 1,024 bytes (8,192 bits) | 1 Kilobyte (KB) | 0 to 2⁸¹⁹² - 1 |

| 2²⁰ | 1,048,576 bytes (8,388,608 bits) | 1 Megabyte (MB) | 0 to 2⁸³⁸⁸⁶⁰⁸ - 1 |

| 2³⁰ | 1,073,741,824 bytes (8,589,934,592 bits) | 1 Gigabyte (GB) | 0 to 2⁸⁵⁸⁹⁹³⁴⁵⁹² - 1 |

| 2⁴⁰ | 1,099,511,627,776 bytes (8,796,093,022,208 bits) | 1 Terabyte (TB) | 0 to 2⁸⁷⁹⁶⁰⁹³⁰²²²⁰⁸ - 1 |

Megabit (Mb) vs Megabyte (MB) vs Mebibyte (MiB)

In computing, there’s a big misconception caused by mixing decimal (base-10) and binary (base-2) systems.

What Does Mega Mean?

“Mega” is a metric prefix meaning 1 million (1,000,000) in base-10.

So:

-

1 Megabit (Mb) = 1 million bits = 1,000,000 bits

-

1 Megabyte (MB) = 1 million bytes = 1,000,000 bytes

Since 1 Byte = 8 bits, this means:

- 1 Megabyte (MB) = 8 Megabits (Mb) = 1 Mb = 0.125 MB

Since ISPs measure in Mb, they make the speed seem 8× larger than what you actually get in megabytes per second (MB/s). Your actual download speed is: 100 Mbps ÷ 8 = 12.5 MB/s

MiB (Mebibyte)

1 MiB = 2²⁰ bytes = 1,048,576 bytes.

Hard drives and ISPs use MB (decimal) to make their numbers look bigger. Computers (OS, programs) use MiB (binary) for accuracy.

So a 500 GB hard drive may show up as 465 GiB in Windows. It’s not missing space, it’s just a different unit system.

Metric Prefixes (Decimal)

| Prefix | Symbol | Power of 10 | Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| yocto | y | 10⁻²⁴ | 0.000000000000000000000001 |

| zepto | z | 10⁻²¹ | 0.000000000000000000001 |

| atto | a | 10⁻¹⁸ | 0.000000000000000001 |

| femto | f | 10⁻¹⁵ | 0.000000000000001 |

| pico | p | 10⁻¹² | 0.000000000001 |

| nano | n | 10⁻⁹ | 0.000000001 |

| micro | µ | 10⁻⁶ | 0.000001 |

| milli | m | 10⁻³ | 0.001 |

| centi | c | 10⁻² | 0.01 |

| deci | d | 10⁻¹ | 0.1 |

| 10⁰ = 1 | 1 | ||

| deca | da | 10¹ | 10 |

| hecto | h | 10² | 100 |

| kilo | k | 10³ | 1,000 |

| mega | M | 10⁶ | 1,000,000 |

| giga | G | 10⁹ | 1,000,000,000 |

| tera | T | 10¹² | 1,000,000,000,000 |

| peta | P | 10¹⁵ | 1,000,000,000,000,000 |

| exa | E | 10¹⁸ | 1,000,000,000,000,000,000 |

| zetta | Z | 10²¹ | 1,000,000,000,000,000,000,000 |

| yotta | Y | 10²⁴ | 1,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000 |

Binary Prefixes

| Prefix | Symbol | Power of 2 | Approx. Decimal Equivalent | Common Use |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| kibi | Ki | 2¹⁰ = 1,024 | ~1.02 × 10³ (1,024) | KiB = kibibyte |

| mebi | Mi | 2²⁰ = 1,048,576 | ~1.05 × 10⁶ | MiB = mebibyte |

| gibi | Gi | 2³⁰ = 1,073,741,824 | ~1.07 × 10⁹ | GiB = gibibyte |

| tebi | Ti | 2⁴⁰ = 1.1 trillion | ~1.10 × 10¹² | TiB = tebibyte |

| pebi | Pi | 2⁵⁰ | ~1.13 × 10¹⁵ | PiB = pebibyte |

| exbi | Ei | 2⁶⁰ | ~1.15 × 10¹⁸ | EiB = exbibyte |

| zebi | Zi | 2⁷⁰ | ~1.18 × 10²¹ | ZiB = zebibyte |

| yobi | Yi | 2⁸⁰ | ~1.21 × 10²⁴ | YiB = yobibyte |

Arithmetic Operations in Binary

Binary arithmetic follows the same basic principles as decimal arithmetic but operates with only two digits: 0 and 1. The four fundamental operations are:

- Binary Addition

- Binary Subtraction

- Binary Multiplication

- Binary Division

1. Binary Addition

Binary addition follows simple rules:

| Binary Addition Rule | Decimal Equivalent |

|---|---|

| 0 + 0 = 0 | 0 + 0 = 0 |

| 0 + 1 = 1 | 0 + 1 = 1 |

| 1 + 0 = 1 | 1 + 0 = 1 |

| 1 + 1 = 10 (write 0, carry 1) | 1 + 1 = 2 |

| 1 + 1 + 1 = 11 (write 1, carry 1) | 1 + 1 + 1 = 3 |

Example of Binary Addition

Let’s add $1011_2\ (11){10}$ + $1101_2\ (13){10}$

1011

+ 1101

--------

11000 (24)_{10}

Steps:

- $1 + 1 = 10$ → write 0, carry 1

- $(1 + 0) + (1 $ we carried$) = 10$ → write 0, carry 1

- $(0 + 1) + (1 $ we carried$) = 10$ → write 0, carry 1

- $(1 + 1) + (1 $ we carried$) = 11$

Result: $11000_2$

2. Binary Subtraction

Binary subtraction follows these rules:

| Binary Subtraction Rule | Decimal Equivalent |

|---|---|

| 0 - 0 = 0 | 0 - 0 = 0 |

| 1 - 0 = 1 | 1 - 0 = 1 |

| 1 - 1 = 0 | 1 - 1 = 0 |

| 0 - 1 = (write 1, borrow 1) | 0 - 1 = -1 |

Example of Binary Subtraction

Let’s subtract $1011_2\ (11){10} - 110_2\ (6){10}$

1011

- 0110

--------

0101 (5)_{10}

Steps:

- $1 - 0 = 1$

- $1 - 1 = 0$

- $0 - 1 = 1$ → write 1, borrow 1

- $(1 - 0) - (1 $ we borrowed$) = 0$

Result: $0101_2$

3. Binary Multiplication

Binary multiplication is like decimal multiplication but follows simpler rules:

| Binary Multiplication Rule | Decimal Equivalent |

|---|---|

| 0 × 0 = 0 | 0 × 0 = 0 |

| 0 × 1 = 0 | 0 × 1 = 0 |

| 1 × 0 = 0 | 1 × 0 = 0 |

| 1 × 1 = 1 | 1 × 1 = 1 |

Example of Binary Multiplication

Let’s multiply $101_2\ (5){10} × 11_2\ (3){10}$

101 (5)

× 11 (3)

------

101 (this is 101 × 1)

+ 101 (this is 101 × 1, shifted left by 1)

------

1111 (15)_{10}

Steps:

- Multiply $101 × 1 = 101$

- Multiply $101 × 1 = 1010$ , shift left

- Result: $101 + 1010 = (1111)_2$

4. Binary Division

Binary division is similar to long division in decimal, but honestly I don’t even know how to do long division XD

Number Base Conversions

In computing, numbers can be represented in various bases (radices), when converting between these systems, the key is to ensure that the representations are equivalent in decimal form.

For example:

$(0011)_8$ and $(1001)_2$ are equivalent because both represent the decimal number 9.

Decimal to Base-r

Method: Repeated Division by the Target Base

- Divide the number by the target base (r).

- Record the remainder.

- Use the quotient for the next division.

- Repeat until the quotient is 0.

- The Answer is the remainders read from bottom to top, left to right.

Example 1.1: Convert (41)_{10} to Binary (Base-2)

41 ÷ 2 = 20 remainder 1

20 ÷ 2 = 10 remainder 0

10 ÷ 2 = 5 remainder 0

5 ÷ 2 = 2 remainder 1

2 ÷ 2 = 1 remainder 0

1 ÷ 2 = 0 remainder 1

Answer: $(41)_{10} = (101001)_2$

Example 1.2: Convert (153)_{10} to Octal (Base-8)

153 ÷ 8 = 19 remainder 1

19 ÷ 8 = 2 remainder 3

2 ÷ 8 = 0 remainder 2

Answer: $(153)_{10} = (231)_8$

Decimal Fractions to Another Base

Method: Repeated Multiplication by the Target Base

- Multiply the fraction by the target base.

- Record the integer part of the result.

- Use the fractional part for the next multiplication.

- Repeat until the fraction becomes 0 (or to the desired precision).

- The Answer is the integer parts read from top to bottom.

Example 1.3: Convert (0.6875)_{10} to Binary (Base-2)

0.6875 × 2 = 1.375 → integer part = 1

0.375 × 2 = 0.75 → integer part = 0

0.75 × 2 = 1.5 → integer part = 1

0.5 × 2 = 1.0 → integer part = 1 (stops here)

Answer: $(0.6875)_{10} = (0.1011)_2$

Example 1.4: Convert (0.513)_{10} to Octal (Base-8)

0.513 × 8 = 4.104 → integer part = 4

0.104 × 8 = 0.832 → integer part = 0

0.832 × 8 = 6.656 → integer part = 6

0.656 × 8 = 5.248 → integer part = 5

0.248 × 8 = 1.984 → integer part = 1

0.984 × 8 = 7.872 → integer part = 7

Answer: $(0.513)_{10} ≈ (0.406517)_8$

Mixed Decimal Numbers to Another Base

When dealing with numbers that have both integer and fractional parts, convert them separately and then combine the results.

Example 1.5: Convert (41.6875)_{10} to Binary

Using previous results:

- $(41)_{10} → (101001)_2$

- $(0.6875)_{10} → (0.1011)_2$

Answer: $(41.6875)_{10} = (101001.1011)_2$

Example 1.6: Convert (153.513)_{10} to Octal

Using previous results:

- $(153)_{10} → (231)_8$

- $(0.513)_{10} → (0.406517)_8$

Answer: $(153.513)_{10} ≈ (231.406517)_8$

Binary to Octal

Example: Convert (101100110110)_2 to Octal

- Group into threes: $(101 100 110 110)_2$

- Convert each group:

- $101 \to 5$

- $100 \to 4$

- $110 \to 6$

- $110 \to 6$

Result: $(5466)_8$

For fractions, group digits to the right of the binary point.

Example: Convert (101100.110)_2 to Octal

- Group into threes: $(101 100 . 110)_2$

- Convert:

- $101 \to 5$

- $100 \to 4$

- $.110 \to .6$

Result: $(54.6)_8$

Binary to Hexadecimal

Example: Convert (101100110110)_2 to Hexadecimal

- Group into fours: $(1011 0011 0110)_2$

- Convert each group:

- $1011 \to B$

- $0011 \to 3$

- $0110 \to 6$

Result: $(B36)_{16}$

For fractions, group digits to the right of the binary point.

Example: Convert (101100.1101)_2 to Hexadecimal

- Group into fours: $(1011 00.1101)_2$

- Convert:

- $1011 \to B$

- $00.1101 \to 0.D$

Result: $(B0.D)_{16}$

Octal & Hexadecimal to Binary

Example: Convert (306.D)₁₆ to Binary

- $3 \to 0011$

- $0 \to 0000$

- $6 \to 0110$

- $D \to 1101$

Result: $(0011 0000 0110.1101)_2$

Example: Convert (673.124)₈ to Binary

- $6 \to 110$

- $7 \to 111$

- $3 \to 011$

- $.1 \to 001$

- $2 \to 010$

- $4 \to 100$

Result: $(110 111 011.001 010 100)_2$

Compact Representation in Computing

Binary numbers are essential for computers but are too long for humans to work with efficiently. This is why:

- Octal is 1/3 the length of binary (every 3 binary digits = 1 octal digit).

- Hexadecimal is 1/4 the length of binary (every 4 binary digits = 1 hex digit).

Example: Compact Representations

- Binary: (1111 1111 1111)_2 (12 digits)

- Octal: (7777)₈ (4 digits)

- Hexadecimal: (FFF)₁₆ (3 digits)

Because of this compactness, many computer manuals and digital system designs prefer hexadecimal over octal since:

- Each byte (8 bits) is represented as two hex digits.

- Hex fits better with modern architectures, which commonly use 8-bit, 16-bit, 32-bit, and 64-bit data representations.

Table: Number System Equivalents (0-15)

| Decimal (10) | Binary (2) | Octal (8) | Hexadecimal (16) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0000 | 00 | 0 |

| 1 | 0001 | 01 | 1 |

| 2 | 0010 | 02 | 2 |

| 3 | 0011 | 03 | 3 |

| 4 | 0100 | 04 | 4 |

| 5 | 0101 | 05 | 5 |

| 6 | 0110 | 06 | 6 |

| 7 | 0111 | 07 | 7 |

| 8 | 1000 | 10 | 8 |

| 9 | 1001 | 11 | 9 |

| 10 | 1010 | 12 | A |

| 11 | 1011 | 13 | B |

| 12 | 1100 | 14 | C |

| 13 | 1101 | 15 | D |

| 14 | 1110 | 16 | E |

| 15 | 1111 | 17 | F |

Unsigned Numbers

An unsigned number can only represent zero and positive numbers (no negative numbers).

The range depends directly on the bit length. For an n-bit number:

- Minimum value: $0$

- Maximum value: $2^n - 1$

Example:

8-bit : 0 to 255

16-bit : 0 to 65,535

32-bit : 0 to 4,294,967,295

64-bit : 0 to 18,446,744,073,709,551,615

Signed Integer

A signed integer can represent both positive and negative numbers.

The most significant bit (MSB) is used as the sign bit. If the sign bit is 1, the number is negative.

If it is 0, the number is positive.

The range of a signed integer depends on its size:

Example (8-bit):

| Binary (8-bit) | Hex | Unsigned Value | Signed Value |

|---|---|---|---|

0000 0000 |

0x00 |

0 |

0 |

0000 0001 |

0x01 |

1 |

1 |

... |

... |

... |

... |

0111 1110 |

0x7E |

126 |

126 |

0111 1111 |

0x7F |

127 |

127 |

1000 0000 |

0x80 |

128 |

-128 |

1000 0001 |

0x81 |

129 |

-127 |

... |

... |

... |

... |

1111 1110 |

0xFE |

254 |

-2 |

1111 1111 |

0xFF |

255 |

-1 |

Complements

Complements are mathematical techniques used in computers to simplify subtraction by converting it to addition. Represent negative numbers. Enable efficient hardware design. No separate subtraction circuit needed (uses same adder).

Magnitude Representation

Use the leftmost bit (MSB) as sign bit

The remaining bits hold the absolute value (magnitude)

Example (8-bit):

+9=00001001-9=10001001

Problem, Two Zeros:

00000000=+010000000=-0

1’s Complement Representation

To get a negative number: flip all bits (bitwise NOT), including the sign bit.

Example:

+9=00001001-9=11110110

Problems, Still Two Zeros:

-

00000000=+0 -

11111111=-0 -

Adds require end-around carry

2’s Complement Representation

To get a negative number: flip all bits (bitwise NOT), including the sign bit, then add 1

Example:

+9 = 00001001

NOT = 11110110 ← 1's complement

+1 = 11110111 ← 2's complement = -9

Advantages:

- Only one zero:

00000000 - same circuits for signed and unsigned

This is what CPUs use

Table Breakdown

| Decimal | 2’s Comp | 1’s Comp | Signed-Mag |

|---|---|---|---|

| +7 | 0111 | 0111 | 0111 |

| +6 | 0110 | 0110 | 0110 |

| … | … | … | … |

| +0 | 0000 | 0000 | 0000 |

| -0 | ❌ | 1111 | 1000 |

| -1 | 1111 | 1110 | 1001 |

| -2 | 1110 | 1101 | 1010 |

| -7 | 1001 | 1000 | 1111 |

| -8 | 1000 | ❌ | ❌ |

Diminished Radix Complement

For a number $N$ in base $r$ with $n$ digits, the $(r-1)’s$ complement is:

$(r^n - 1) - N$

Decimal (9’s Complement)

$Base\ r = 10 → (r-1) = 9 → 9’s\ complement$

$9’s\ complement\ of\ N = (10^n - 1) - N$

Since $( 10^n - 1 )$ is just a number with $n\ 9s$ Subtract each digit of $N$ from $9$

Examples:

- 9’s complement of $546700$ $=$ $999999 - 546700 = 453299$

- 9’s complement of $012398$ $=$ $999999 - 012398 = 987601$

Binary (1’s Complement)

$Base\ r = 2 → (r-1) = 1 → 1’s\ complement$

$1’s\ complement\ of\ N = (2^n - 1) - N$

Since $( 2^n - 1 )$ is just a number with $n\ 1s$

Flip each bit:

- $ 1 → 0$

- $ 0 → 1$

Examples:

- 1’s complement of $1011000 = 0100111$

- 1’s complement of $0101101 = 1010010$

Radix Complement

The $r’s\ complement$ of an $n$-digit number $N$ in base $r$ is

$(r^n - N)$ for $N > 0$, and $0$ if $N = 0$

It is equivalent to:

$r’s complement\ = (r-1)’s\ complement\ + 1$

Decimal (10’s Complement)

$Base\ r = 10$

$10’s\ complement\ of\ N\ = (10^n - N)$

since $r^n - N = [(r^n - 1) - N] + 1$ thus, the 10’s complement is obtained by adding $1$ to the $9’s$ complement value.

Binary (2’s Complement)

$Base\ r = 2$

$2’s\ complement\ of\ N\ = (2^n - N)$

Equivalent to:

$1’s\ complement\ of\ N\ + 1$

Leading Zeros

In positional number systems (binary, decimal, hexadecimal, etc) leading zeros do not affect the value of a number.

Decimal:

... 000,000,000,000,000,000,001,234 = 1,234

Binary:

... 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 1011 0101 = 1011 0101

Hexadecimal:

... 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 003F 2D1F = 0x3F2D1F

Sign Extension

In two’s complement representation (used for signed integers), the leftmost bit is the sign bit (0 = positive, 1 = negative). When extending the bit-width of a two’s complement number:

- For positive numbers, pad with leading

0s. - For negative numbers, pad with leading

1s.

This is called sign extension, and it preserves the original value while increasing the number of bits.

Examples:

Positive Number (5 in 4-bit → 8-bit):

- Original:

0101(4-bit,5in decimal). - Extended:

00000101(8-bit, still5). - Leading

0s can be ignored:101is still5if context is clear.

Negative Number (-5 in 4-bit → 8-bit):

- Original 4-bit:

1011(two’s complement for-5: invert0101+1=1011). - Extended 8-bit:

11111011(still-5). - Leading

1s can be ignored if the bit-width is fixed/implied (1011and11111011both represent-5in their respective sizes).

Bit Weights in 2’s Complement

In standard unsigned binary, each bit represents a power of $2$ (right to left, starting at $2^0$):

128 64 32 16 8 4 2 1 (for 8-bit)

But in two’s complement signed numbers, the leftmost bit (MSB) has a negative weight:

-128 64 32 16 8 4 2 1 (for 8-bit)

- If the MSB is

1, the number is negative. - If the MSB is

0, the number is positive (same as unsigned).

Example 1: 11111011 (8-bit) → -5

Let’s decode 11111011 using bit weights:

Bit position: [7] [6] [5] [4] [3] [2] [1] [0]

Bit value: 1 1 1 1 1 0 1 1

Weight: -128 64 32 16 8 4 2 1

Now, multiply each bit by its weight and sum:

= (1 × -128) + (1 × 64) + (1 × 32) + (1 × 16) + (1 × 8) + (0 × 4) + (1 × 2) + (1 × 1)

= -128 + 64 + 32 + 16 + 8 + 0 + 2 + 1

= -128 + (64 + 32 + 16 + 8 + 2 + 1)

= -128 + 123

= -5

Example 2: 1011 (4-bit) → -5

For 4-bit two’s complement, the weights are:

-8 4 2 1

Now decode 1011:

= (1 × -8) + (0 × 4) + (1 × 2) + (1 × 1)

= -8 + 0 + 2 + 1

= -5

Subtraction with Complements

Instead of subtracting $N$, you add its complement

Add the minuend $M$ to the r’s complement of the subtrahend $N$

$M + (r^n - N) = M - N + r^n$

Now two possibilities:

-

If $M ≥ N$ the sum will be $≥ r^n$, and the carry happens. You discard the carry, and the rest is the correct answer.

-

If $M < N$ the sum is $< r^n$, so no carry happens, and the result is in r’s complement form (a negative number in disguise). You take the r’s complement again to find its magnitude and place a negative sign in front.

Example 1.1

Using 10’s complement, subtract $72532 - 3250$

$M = 72532$

$N = 03250$ (we pad it to 5 digits)

$r^5 = 100000$ So 10’s complement of $03250 = 100000 - 03250 = 96750$

- Why this? cuz adding $96750$ to $M$ is like subtracting $03250$ (but easier for the computer).

$M$ + 10’s complement of $N = 72532 + 96750 = 169282$

Check for carry

The result is $> 100000$ so carry occurred $M ≥ N$ So discard the carry (subtract 100000):

$169282 - 100000 = 69282$

Final answer: $69282$

- Why discard the carry? Because it’s the extra $r^n$ we added earlier to help convert subtraction to addition. It’s not part of the actual difference.

Example 1.2

Using 10’s complement, subtract $3250 - 72532$

We need to make sure both numbers have the same number of digits to work with complements.

$M = 3250$

We pad it with leading zeros to make it 5 digits: $M = 03250$

$N = 72532$

This already has 5 digits, so no padding needed.

To subtract using complements, we first need to find the 10’s complement of $N$. The 10’s complement is found by subtracting the number from $10^n$ (where $n$ is the number of digits).

$N = 72532$ (5 digits)

$10^5 = 100000$

So, the 10’s complement of N is:

- $10^5 - N = 100000 - 72532 = 27468$

Now, we add $M$ to the 10’s complement of $N$:

The sum is: $30718$

Check for End Carry

-

If there is an end carry, we discard it and take the result as positive.

-

If there is no end carry, we know that the result is negative, and we take the complement of the result to find the negative value.

So

-

The sum is $30718$, and there is no end carry (the sum is less than $100000$). Take the 10’s Complement of the Result

-

$10^5 - 30718 = 100000 - 30718 = 69282$

Now, we place a negative sign in front of the result: $-69282$

Example 1.3

Given the two binary numbers $X = 1010100$ and $Y = 1000011$

perform the subtraction

$X - Y$ and $Y - X$ by using 2’s complements.

X - Y

Find 2’s complement of $Y = 1000011$

So $-Y = 0111101$

then add $X$ and $-Y$

Sum $= 10010001$

Discard end carry $2^7 = 10000000$

Answer: $X - Y =$ Sum $- 10000000 = 0010001$

Y - X

2’s complement of $X = 1010100$

$-X = 0101100$

then add $Y$ and $-X$

Sum $= 1101110$

There is no end carry. Therefore, the answer is $Y - X = -(1’s$ complement of $1101110) = -0010001$

Discard End Carry (in 2’s complement)

If there’s a carry-out (bit too big to fit), you just throw it away.

Why? Because in 2’s complement, the carry-out isn’t needed, the result is already correct due to how 2’s complement encodes negatives.

Example (4-bit):

0110 = 6

+ 1101 = -3 (in 2's comp)

-------

1 0011 ← Carry-out = 1

Discard carry: result $= 0011 = 3$

End-Around Carry (in 1’s complement)

Instead of discarding the carry, you add it back into the result.

Why? Because 1’s complement doesn’t fully represent negatives. Adding back the carry fixes the incomplete math.

Example (4-bit):

0110 = 6

+ 1100 = 1's comp of 3

-------

1 0010 ← Carry-out = 1

Add carry back:

- $0010 + 1 = 0011 = 3$

BCD

Let’s say you want to store the number 47.

In normal binary, 47 is:

$101111$ (this is pure binary, stores whole number at once)

But in BCD, we store each digit (4 and 7) in binary separately:

- 4 →

0100 - 7 →

0111

So BCD for 47 is: 0100 0111

Why? Because humans use decimal, and BCD keeps it close to human format, easy to display on screens, calculators, etc.

Valid and Invalid BCD

BCD only allows values 0–9 per 4 bits:

0000= 00001= 1

…1001= 9

Invalid BCD: 1010 to 1111 (decimal 10–15) → these must never appear as-is in BCD.

Adding BCD Digits

Say you want to do:

8 + 9

In BCD:

- 8 →

1000 - 9 →

1001

We add like binary:

1000

+ 1001

-------

10001

That’s binary 17, which is wrong in BCD, we can’t represent 17 directly.

So we must fix it by adding 6 (0110):

10001 + 0110 = 10111

- Now we have a carry (

1) - And the final BCD digit =

0111→ which is 7

So the final result is carry 1, BCD 0111 → 17

Why Add 6 (0110) Exactly?

Because:

- BCD max valid digit = 9 →

1001 - Any sum ≥ 10 = invalid

- The difference between 16 and 10 = 6. So adding 6 adjusts the result to the right carry and digit

Another Example: 4 + 8

BCD:

- 4 →

0100 - 8 →

1000

Add:

0100

+ 1000

-------

1100 → decimal 12 ❌

Invalid BCD, so add 0110:

1100 + 0110 = 10010

Now:

- carry = 1

- sum =

0010→ which is 2

Final result = carry 1, BCD 2 → means 12

Gray Code

also known as Reflected Binary Code, is a binary numeral system where two successive values differ in only one bit. This unique property makes it especially useful in digital electronics to prevent errors when values change from one state to another.

In regular binary counting, multiple bits may change at once (0111 → 1000 flips all 4 bits). This can cause transient errors during physical switching.

Gray code solves this by ensuring only one bit changes at a time, reducing the chance of glitches due to timing mismatches.

Reflective Method (for n-bit Gray code):

-

Start with 1-bit:

0and1. -

Reflect the existing code (reverse the list).

-

Prefix

0to the original, and1to the reflected list. -

Repeat for n bits.

Example: 3-bit Gray Code

| Binary | Gray Code |

|---|---|

| 000 | 000 |

| 001 | 001 |

| 010 | 011 |

| 011 | 010 |

| 100 | 110 |

| 101 | 111 |

| 110 | 101 |

| 111 | 100 |

Binary to Gray Code

- First Gray bit = First Binary bit

- Rest:

G[i] = B[i] XOR B[i-1]

Example: Convert 1011 to Gray

G1 = B1 = 1

G2 = B2 ⊕ B1 = 0 ⊕ 1 = 1

G3 = B3 ⊕ B2 = 1 ⊕ 0 = 1

G4 = B4 ⊕ B3 = 1 ⊕ 1 = 0

Gray = 1110

Gray Code to Binary

- First Binary bit = First Gray bit

- Rest:

B[i] = B[i-1] XOR G[i]

Example: Convert 1110 to Binary

B1 = G1 = 1

B2 = B1 ⊕ G2 = 1 ⊕ 1 = 0

B3 = B2 ⊕ G3 = 0 ⊕ 1 = 1

B4 = B3 ⊕ G4 = 1 ⊕ 0 = 1

Binary = 1011

Why Only One Bit Changes?

In hardware (mechanical switches or sensors), multiple bit transitions at once can cause ambiguous readings during the moment bits are changing so if only one bit changes, there’s no ambiguity, and the signal is clean and reliable.

Endianness

The word “endianness” itself comes from the term “endian”, which was coined in reference to Gulliver’s Travels by Jonathan Swift. In the book, there is a fictional conflict between two factions: one that breaks their eggs at the small end and another that breaks them at the large end. This is an allegory about a seemingly trivial difference leading to a huge conflict.

In computing, “endianness” refers to the way in which multi-byte data is stored in memory, whether the most significant byte (MSB) (big-endian) or the least significant byte (LSB) (little-endian) is stored first.

Big Endian

In big-endian systems, the most significant byte (MSB) is stored at the lowest memory address (at the beginning of the data). So, for a multi-byte value like a 32-bit integer, the most significant part of the number (the leftmost byte) comes first.

Example:

Let’s take the 32-bit integer 0x01020304. In Big Endian, the bytes would be stored in memory like this:

Address: 0x00 0x01 0x02 0x03

Value: 0x01 0x02 0x03 0x04

In this case, 0x01 is the most significant byte (MSB) and is stored at the lowest memory address (0x00).

Little Endian

In little-endian systems, the least significant byte (LSB) is stored at the lowest memory address. This means that for multi-byte values, the rightmost byte (the least significant byte) comes first.

Example:

Now, let’s look at the same 32-bit integer 0x01020304. In Little Endian, the bytes would be stored in memory like this:

Address: 0x00 0x01 0x02 0x03

Value: 0x04 0x03 0x02 0x01

Here, 0x04 (the least significant byte) is stored at the lowest memory address (0x00).

ASCII

stands for the American Standard Code for Information Interchange.

uses a 7-bit binary system, which means it can represent 128 characters (from 0 to 127). This was enough for the English language, including letters, digits, punctuation, and a few control characters (like newline, tab, and carriage return).

but it can only represent 128 characters. This isn’t enough to represent characters from all languages around the world, especially when languages have thousands of characters (Chinese, Japanese, Arabic, etc).

Code Pages

To solve this limitation of 128 characters, we get Code Pages.

A Code Page is essentially a mapping of values (numbers) to characters.

The idea is to use the unused values (128–255) from the 8-bit range (1 byte) to add more characters to the encoding.

Example of Code Pages:

ISO/IEC 8859-1 (also called Latin-1) is a code page for Western European languages (like French, German, Spanish, etc.).

It uses values from 128 to 255 to represent accented characters like é or ñ.

Windows-1252 is another code page used for Western European languages.

The issue with code pages is that they are limited to a region. For example, Windows-1251 is used for Cyrillic (Russian), and it won’t work for Chinese, Japanese, or Arabic characters. Each code page is designed for a specific language group, and you can’t easily switch between them.

Multibyte Character Sets

For languages that have more than 256 characters, you need a way to represent thousands of characters.

This is where Multibyte Character Sets come into play.

Instead of using 1 byte (8 bits) per character, we use multiple bytes to represent a single character.

So, one character might take 2 bytes, 3 bytes, or even more depending on the language and character.

Examples of Multibyte Encoding:

Shift-JIS: This is a multibyte encoding for Japanese characters. It uses both 1 byte (for ASCII characters) and 2 bytes (for kanji, hiragana, and katakana characters).

GB2312: This is a multibyte encoding for Simplified Chinese. It uses 2 bytes for most characters.

However, multibyte character sets are not perfect, and they can be tricky to handle because:

- They don’t always define how to handle byte sequences correctly.

- They are not universal and are region-dependent (for example, Shift-JIS is for Japanese, not for other languages).

Unicode

Unicode is a universal character encoding standard. Its goal is to represent every character in every language ever written, including ancient languages (like Egyptian hieroglyphs) and constructed languages (like Klingon or Esperanto).

Unicode Code Points

Each character in Unicode is assigned a unique identifier called a code point.

A code point is usually written in the format U+XXXX, where XXXX is the hexadecimal value of the code point.

There are different encodings that determine how Unicode characters are stored in memory or files. The most common are UTF-8, UTF-16, and UTF-32.

UTF-8

Variable-Length Encoding: UTF-8 uses 1 to 4 bytes to represent a character.

Characters in the ASCII range (U+0000 to U+007F) use 1 byte, making UTF-8 compatible with ASCII.

Non-ASCII characters (like Chinese or emoji) use 2, 3, or 4 bytes. Advantage: It’s space-efficient for English text and backward-compatible with ASCII.

Example:

The letter A (U+0041) in UTF-8 is just 0x41 (1 byte).

The Chinese character 字 (U+5B57) in UTF-8 is 0xE5 0xAD 0x97 (3 bytes).

UTF-16

Fixed-Length Encoding for Most Characters: UTF-16 uses 2 bytes for most characters. However, it can use 4 bytes for some rare characters (those outside the Basic Multilingual Plane).

Advantage: UTF-16 is more efficient for languages with a lot of characters, like Chinese or Japanese, because it uses fewer bytes for these characters compared to UTF-8.

Example:

- The letter A (

U+0041) in UTF-16 is0x0041(2 bytes). - The Chinese character 字 (

U+5B57) in UTF-16 is0x5B57(2 bytes).

UTF-32

Fixed-Length Encoding: UTF-32 uses 4 bytes for every character, no matter how simple or complex it is.

Every character is represented by exactly 4 bytes, making it easy to calculate the size of a string. but it’s very space-inefficient because even simple characters like “A” use 4 bytes.

Example:

- The letter A (

U+0041) in UTF-32 is0x00000041(4 bytes). - The Chinese character 字 (

U+5B57) in UTF-32 is0x00005B57(4 bytes).

Variable Binary Length Data

In many communication protocols, data doesn’t always fit neatly into a fixed-size format. Imagine you have a username for authentication. Some usernames might be very short (like “Bob”), while others could be much longer (like “SuperUltraMegaUser123”). If we try to store these in a fixed-length format (always 16 characters), we end up wasting space for shorter usernames or might run out of space for longer usernames. This is where variable-length data comes in.

It’s more efficient because it uses exactly as much space as needed for the data.

Now, protocols that transmit data over a network often need to handle these variable-length data values efficiently.

Terminated Data

Each data element has a special marker (a terminating symbol) that tells the system where the data ends. You’ve probably encountered this with strings where there is a special symbol like a null character (NUL) to mark the end of the string.

Example of a Terminated String (NUL-terminated):

Data: H e l l o

Hexadecimal representation: 0x48 0x65 0x6C 0x6C 0x6F

NUL terminator: 0x00

The string “Hello” is stored as a sequence of bytes, and the NUL value 0x00 marks the end of the string.

The NUL character is not typically part of a string, so it’s safe to use it as a marker to end the string. When the protocol reads data, it stops reading as soon as it encounters 0x00 (the NUL terminator).

If the data itself contains a 0x00 byte (for example, in some binary data), it could prematurely signal the end of the string. It escaped with a special symbol like a backslash (\0) or repeated 0x00 to signal that it’s not the terminator but part of the string.

Bounded Data

Another method where you specify a start and end marker. In this case, the data is surrounded by specific characters that mark where the data begins and ends.

Binary Logic

binary logic uses two values (0 and 1), which represent things like:

- True/False

- Yes/No

- High/Low voltage

Binary logic is an application of Boolean algebra, which is basically math where: The only values are 1 and 0

Binary Storage

A binary cell is a device with two stable states.

It can store one bit of information: either a 0 or a 1. Each cell has:

Inputs: They receive excitation signals (signals that control the state).

Output: A physical signal (like voltage) that tells us if the stored bit is a 0 or 1.

One binary cell = one bit of memory.

Register

A register is a group of binary cells (bits). If a register has n cells, it can store an n-bit binary value. The state of the register is the set of all its bits, written as an n-tuple of 0s and 1s.

Example: 16-bit Register

Let’s say the register holds:

1100001111001001

This register: Has 16 bits, Can hold 2^16 = 65,536 different values that can be interpreted in different ways:

The same bit pattern can represent different types of data depending on the application.

Register Transfer

Digital systems use registers + logic circuits to process binary data.

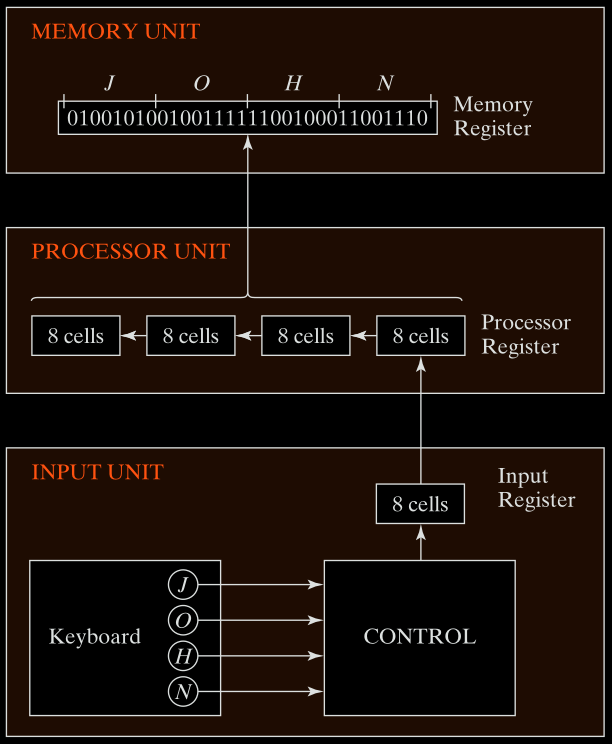

Input Example (from Keyboard to Memory)

Fig. 1-1 below describes how characters entered from a keyboard are transferred:

- Keyboard sends character → Control circuit converts it to 8-bit ASCII code.

- ASCII character goes into the Input Register.

- Then, it is transferred to the Processor Register (the 8 rightmost bits).

- Existing content in the Processor Register is shifted left by 8 bits.

- After 4 characters (J, O, H, N) → Processor Register is full.

- The content is moved to Memory Register for storage.

Final stored bits in memory for “JOHN”:

01001010 01001111 01001000 01001110

Binary Information Processing

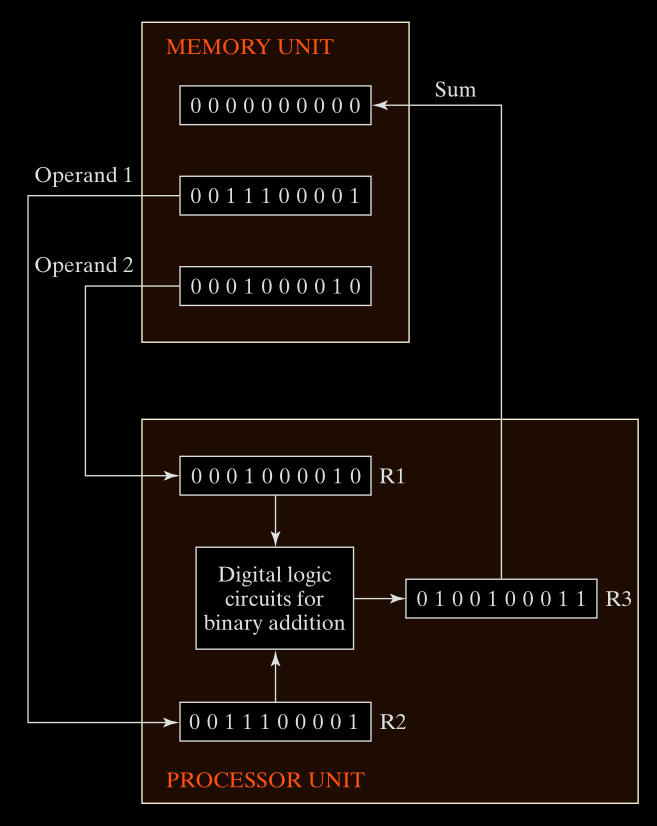

Fig. 1-2 below shows binary addition using processor registers:

-

Memory contains two 10-bit binary numbers:

- Operand 1 =

0011100001= 225 - Operand 2 =

0001000010= 66

- Operand 1 =

-

These are loaded into processor registers

R1andR2. -

The digital logic circuits add the two:

R3 = R1 + R2 = 225 + 66 = 291- In binary:

0100100011

-

Result (

R3) can be written back to memory.

Memory stores data, processors manipulate data using registers and logic.